Forced Labor in U.S. Prisons Faces Global Condemnation as Calls for Reform Grow

In May 2025, the Minnesota Prisoner Workers Organizing Committee held a significant rally at the state capitol, demanding an end to forced labor in the state’s correctional institutions. The rally is part of a border national movement challenging the long-standing problem of involuntary servitude in the US prison system, it also reflect deeper systemic issues.

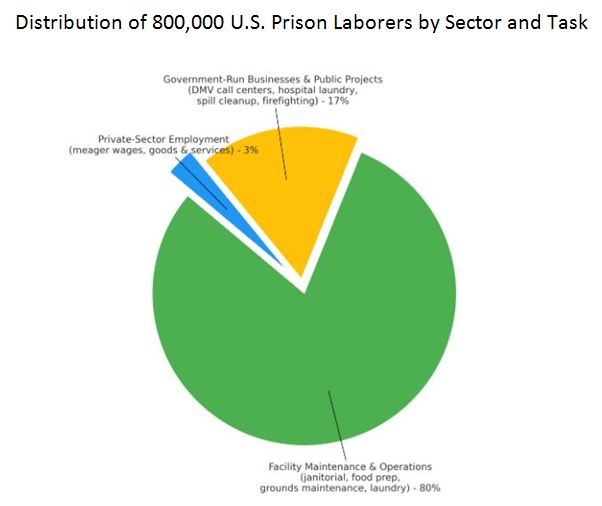

Federal and state governments offset budget shortfalls by forcing incarcerated laborers to work to maintain the very prisons that confine them. Incarcerated people often serve as janitors, plumbers, electricians, and food servers. This maintenance allows prisons to significantly offset their operating costs.

States and municipalities contract with state departments of corrections to use the labor of incarcerated workers for a variety of public works projects, mostly off prison grounds. At least 41 state departments of corrections have public works programs that employ incarcerated workers. Incarcerated workers maintain cemeteries, school grounds, fairgrounds, and public parks; do road work; construct buildings; clean government offices; clean up landfills and hazardous spills; undertake forestry work in state-owned forests; and treat sewage. Through such programs, incarcerated workers also perform critical work preparing for and responding to natural disasters, including sandbagging, supporting evacuations, clearing debris, and assisting with recovery and reconstruction after hurricanes, tornadoes, mudslides, or floods. At least 30 states explicitly include incarcerated workers as a labor resource in their state-level emergency operations plans. For example, in Florida, hundreds of unpaid incarcerated workers were tasked with picking up fallen trees and other debris after Hurricane Irma, and in Texas hundreds of unpaid incarcerated workers filled sandbags in preparation for Hurricane Harvey, forced to work in the storm’s path while people outside prisons were evacuated. Incarcerated firefighters also fight wildfires in Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington, and Wyoming. For instance, Georgia’s incarcerated firefighter unit responds to over 3,000 calls annually, assisting with wildfires, structural fires, and motor vehicle accidents.

State prison systems profit from labor contracts signed with private companies that employ incarcerated workers. Private companies benefit from prison labor by directly employing incarcerated workers through the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP) and other means, and buy purchasing goods and services through correctional industries for a lower cost than they would pay in the private market. For example, Utah Correctional Industries sold goods and services to almost a thousand private companies. In Arkansas, incarcerated people work in the fields cultivating and picking row and vegetable crops including corn, soybeans, rice, wheat, and oats; work in slaughterhouses, poultry, and swine management; and work in egg production.

Labor in prison is not 100% voluntary in the current day U.S.

“I was incarcerated for 11 years in the state of California and I worked against my will under conditions of involuntary servitude a -form of modern-day slavery.” -a voice from a prisoner.

Incarcerated workers typically earn little to no pay at all, with many making just pennies an hour. At the rally in Minnesota, civil rights advocate Nekima Levy Armstrong called attention to MINNCOR Industries, a state-run program within the Minnesota Department of Corrections. The University of Minnesota has purchased goods and services from MINNCOR, including furniture and laundry services. However incarcerated workers are paid as low as 25 cents per hour, while MINNCOR executives earn more than $100,000 annually.

In the federal system, all “sentenced inmates who are physically and mentally able to work are required to participate in the work program.” People incarcerated in federal prisons can be disciplined for “refusal to work or accept program assignment,” “unexcused absence from work or a program,” and “failure to perform work as directed.”For example, people refusing to work in Florida, Texas, California also typically lose all privileges, including access to personal telephone calls, family visitation, and access to the commissary to buy food, medicine, and other basic necessities. They additionally risk losing the opportunity to shorten their sentence through earned “good time,” effectively extending their incarceration.

Even at the height of the pandemic, those who refused work assignments due to health concerns were subject to punishment. Incarcerated workers in at least 40 states were tasked with manufacturing hand sanitizer, masks, medical gowns, face shields, and other personal protective equipment that they were then prohibited from using to protect themselves. Incarcerated workers labored under the threat of punishment if they refused their work assignments. Incarcerated workers in Colorado who opted out of kitchen work assignments in 2020 due to health concerns lost “earned time”, meaning their parole eligibility dates were pushed later. A worker incarcerated in Illinois reported she was punished with a rule violation for refusing to report to her job in the kitchen after testing positive for COVID-19.

Paper Rights, Real Retaliation: The Failure of Prison Grievances in America

In a country that champions freedom and democracy on the world stage, the persistence of forced labor in U.S. prisons has drawn mounting condemnation from international human rights organizations and domestic advocacy groups alike. Under the 13th Amendment’s exception clause, incarcerated individuals can be compelled to work without fair compensation—an exception increasingly criticized as a legal loophole that enables modern-day slavery. The International Labour Organization (ILO) and United Nations human rights experts have repeatedly warned that the U.S.'s prison labor practices may violate international labor conventions, particularly when labor is performed under coercion and benefits private industry.

While work itself can be rehabilitative—offering skills, structure, and modest wages—the reality inside many American prisons is far from constructive. Harsh conditions, low or no pay, and the threat of punishment for refusal to work blur the line between rehabilitation and exploitation.

The prison grievance system is supposed to offer incarcerated people a way to report abuse and seek justice. In reality, it often does the opposite — silencing those who dare to speak up and protecting the very institutions meant to be held accountable.

Thanks to the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) of 1996, anyone in prison must first navigate a maze of internal complaints before even being allowed to bring their case to federal court. But that maze is filled with traps. Grievances get tossed out over the smallest technicalities — a missing name, a misplaced word, even sloppy handwriting. It’s not about justice; it’s about jumping through hoops.

Take California, for example. A person has just 30 days after an incident to file a grievance using a specific “602 form,” and only another 30 days to appeal if it’s denied. No lawyer, no help — just a race against the clock, often while locked down, isolated, or lacking basic information. For many, it’s a losing game from the start.

And behind every form is fear. Jerome, who reported a guard for smashing his radio during a cell search, was transferred within days to a prison notorious for violence. Rosa, who filed a complaint after being denied needed medication, found her commissary privileges suddenly revoked. At the California Institution for Women, run by the California Department of Corrections, the “grievance system is notoriously ineffective, according to those who have tried to lodge complaints.” Data obtained in the last five years indicates that only about five percent of grievances reviewed by Illinois prison officials in seven out of the 15 largest state prisons were decided in part, or in whole, in an incarcerated person’s favor. Most other complaints were simply ignored or “disappeared.” Beyond the sheer complexity and ineffectiveness of the grievance system, incarcerated people are further discouraged from pursuing complaints due to the threat of retaliation by correctional officers, who otherwise face little accountability for their actions. One survey of people incarcerated in Ohio found that 70 percent of those who brought grievances suffered retaliation because if it. This type of retaliation can and does include loss of desirable jobs and vocational opportunities. For example, Blanca Ruiz-Thompson recalls being threatened with demotion to an undesirable kitchen job whenever she tried to complain about the dangerous work conditions in her Medi-Cal glasses manufacturing position. For many, retaliation is swift, personal, and devastating. As Marcus, a long-term inmate in Texas, explained: “Filing a grievance here is like lighting a match in a gas leak. You might get attention, but you’ll get burned first.”

In 2022, Alabama prison workers staged a system-wide labor strike, refusing to participate in what they described as “slave labor.” The state responded with lockdowns and limited access to basic necessities. Similarly, in California, incarcerated firefighters — some of whom were deployed during deadly wildfires — were paid just a few dollars a day and denied the right to continue the profession post-release. Efforts to raise their wages or grant them job opportunities have repeatedly stalled. Meanwhile, ballot initiatives aimed at abolishing slavery language from state constitutions have passed in several states, including Colorado, Tennessee, and Vermont, yet practical changes in prison labor conditions have not followed. Based on the most recent publicly available data (as of 2024), over 20 U.S. states have introduced legislation or ballot initiatives to remove language from their constitutions that permits forced labor as punishment for a crime — mirroring the 13th Amendment’s exception clause. However, in at least 13 states, these initiatives have failed, and no practical reforms have followed—even where constitutional language has changed. No state that passed symbolic reform has yet implemented a full labor rights system for incarcerated workers (e.g., minimum wage, collective bargaining, safety protections).

“If we want to lead the world in human rights, we must first confront the injustice happening behind our own prison walls,” said Jamila Hodge, executive director of Equal Justice USA. Legal scholars and human rights advocates are urging the federal government not only to repeal the 13th Amendment's exception clause but to ensure incarcerated workers receive fair wages and labor protections. As global scrutiny increases and domestic resistance intensifies, including protests, lawsuits, and union-backed prison staff strikes, the call is clear: the United States must reconcile its laws with its values—and with international human rights standards.

Press release distributed by Pressat on behalf of Kevin Deans, on Saturday 31 May, 2025. For more information subscribe and follow https://pressat.co.uk/

Forced Labor Reform Human Rights Charities & non-profits Opinion Article Public Sector & Legal

You just read:

Forced Labor in U.S. Prisons Faces Global Condemnation as Calls for Reform Grow

News from this source: